gustav elgin |art critic

The story goes: On varnishing day, the final day before the opening of the Royal Academy's annual summer exhibition in London, renowned romanticist painter William Turner would present an unfinished, seemingly abstract, painting to his fellow academy members. Then, at the last possible minute, with the flick of a wrist, he would paint a detail pulling the abstract composition into figuration. The mast of a boat revealing a seascape at sunset, the exhaust pipe of a locomotive revealing train tracks on a misty morning.

Turner’s effort to discover the minimum, that watershed moment when canvas and paint transform into painting, echoes throughout the multi-disciplinary practice of South-Korean artist Heeza Bahc. Her first major series, Art School Project (2015), photographically documents the stairwells, classroom corners, and other interstitial spaces of a Viennese art school. At the time of the work's completion, Bahc was herself in transition, having recently left her work as a media photographer to pursue a career in art. Her photographs, much like Turner's canvases, had to transform into artworks. The series alludes to this metamorphosis not only in the subject matter – stairwells and archways famously symbolizing change – but in the particular way the photograph Nr29cz is mounted: Its two-dimensional pictorial field yields to gravity and unfurls into space. The recognition of the picture support becomes the moment where photography acknowledges that it documents not only its subject, but itself. It is, in other words, an original. The transformation is complete.

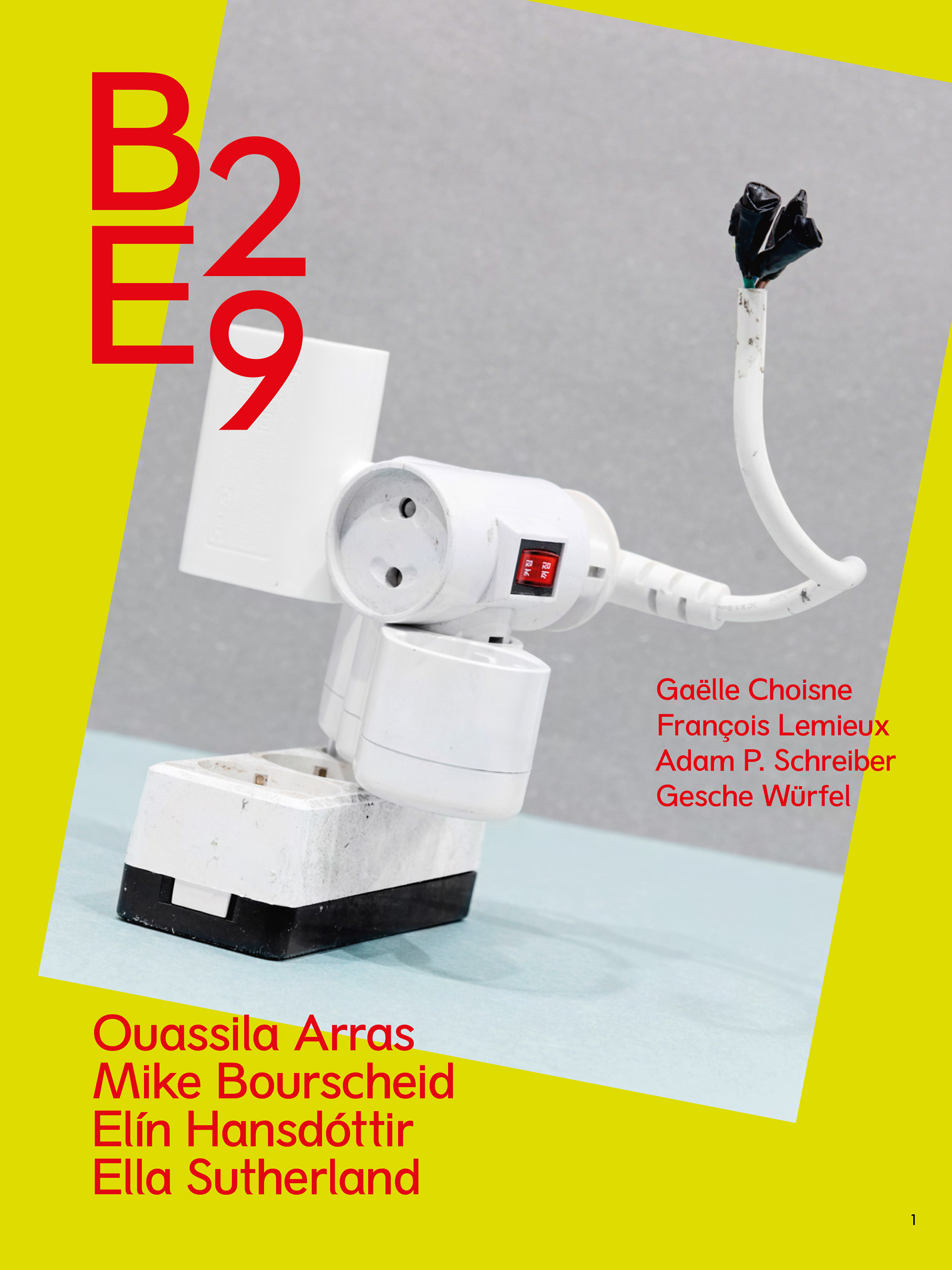

For Bahc, documenting transitional moments and spaces is intrinsically linked to bringing the peripheral into focus. In Displaced Objects (2018) Bahc assembles old picture frames, electrical wires, and other industrial remnants found in the streets of Seoul's once bustling industrial center of Euljiro into sculptural collages, that are then photographed and framed or presented as sculptural installations. Her process is more akin to salvaging than to that of recycling, for while recycling often reformulates material, salvaging retains the former identity. Here, Bahc allows for the past identity of a peripheral cityscape to enter into dialogue with the present.

It is not lost on Bahc that bringing the periphery into view paradoxically destroys its status as periphery and, in turn, generates new framings. In an addendum to Displaced Objects, miniatures of the original installations are mounted on a rotating motor, making what was previously part of the work's social framework – the circling of a viewer – part of its internal logic. In Performer (2019), Bahc invites a dancer to interact with objects from previous projects, which visitors may experience through a VR-headset. The reception of the work is outsourced to a body double, and again the lens widens: What was once in the periphery of the art experience becomes part of the work itself.

Peripheries, as Bahc continuously demonstrates, are bound to geographical and architectural space. People who have only visited the ground floor of Künstlerhaus Bethanien will be unaware of the bright blue, green and yellow staircases that serve as the intestines between the studios, office and exhibition space. This invisible yet integral part of the metabolic system of Künstlerhaus Bethanien will be the focal point of Bahc's latest work. At the time of writing, the project remains unnamed – still in that transformative state before concept turns into artwork.